On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

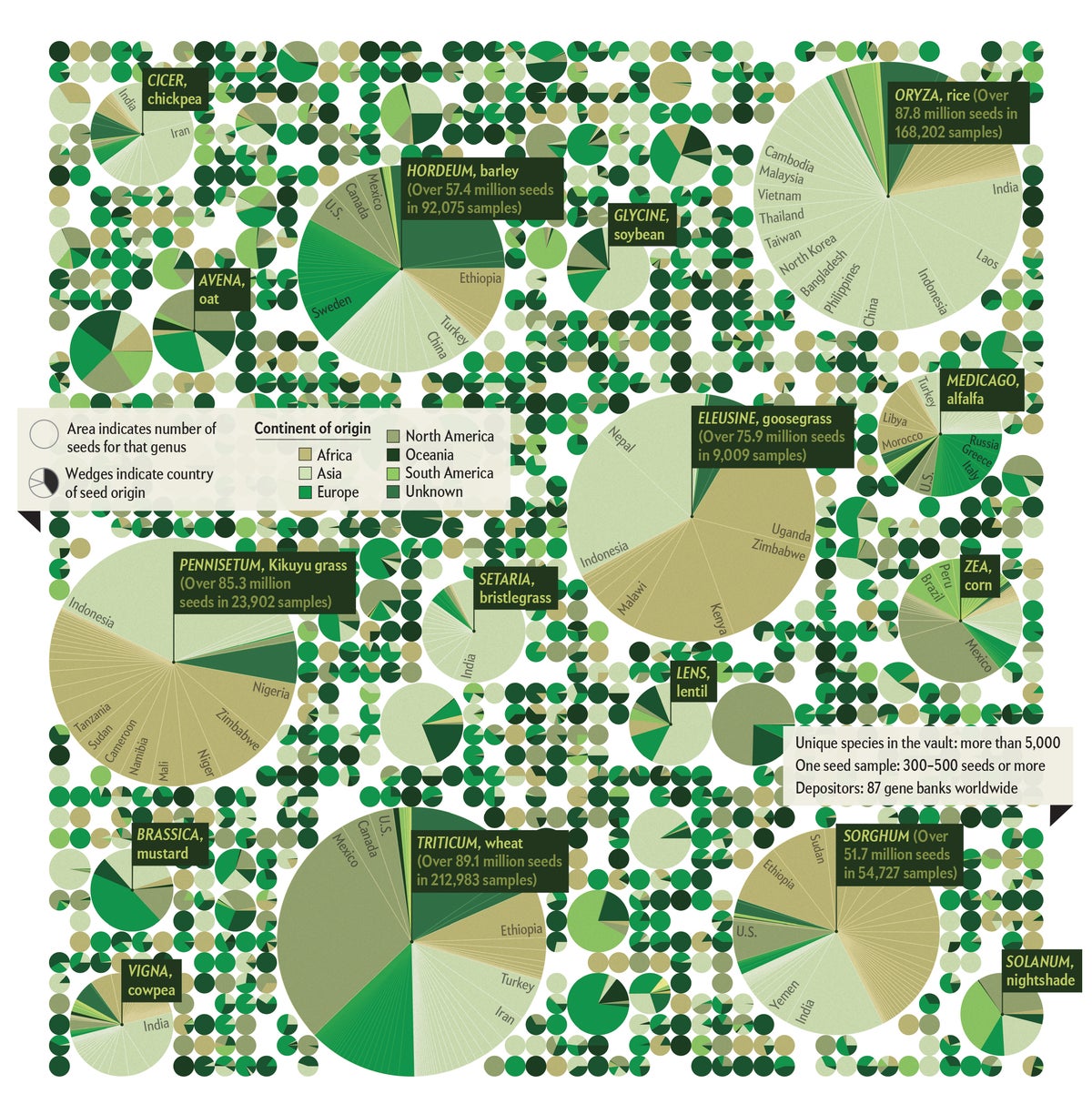

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault recently received seeds from 33 countries, pushing the total number of samples stored there to 1.05 million. Each sample is a pouch of seeds belonging to one genotype; pouches sit on shelves in large rooms carved from solid rock 100 meters inside a mountain covered by permafrost and ice on Spitsbergen island far north of Norway. Some 87 gene banks use the vault to store duplicates of seeds from numerous countries and First Peoples that are important to crops and rangeland grasses, their wild relatives, and experimental species from breeders that might improve plant yield or resilience—primarily to back up food supply against threats from climate change and biodiversity loss. The frozen ground keeps the vault at −3 degrees Celsius; cooling systems deepen the chill to −18 degrees C.

Credit: Accurat (Giovanni Magni, Stefania Guerra, Antonella Autuori and Luca Mattiazzi); Source: Svalbard Global Seed Vault